Instruction Set Architecture: Part 1 - Classification

Let's start by asking the following questions: what the hell is an instruction set architecture (ISA), and why does it matter? For starters, the ISA is the interface between hardware and software. This is of particular importance because it determines what type of computer will be built and how it will perform. In other words, the ISA determines the set of instructions a particular processor can execute. By extension, this also includes the study of different instruction formats, types of addressing modes, and the assembly language support.

The ISA defines many things, including but not limited to program state, semantics, and formatting. These will be covered later, but for now, let's look at how ISAs are typically classified as.

Defining Some Key Terminology

Before we begin our discussion regarding ISAs, some key terminology will have to be defined:

- Memory

- Within the context of not only computer architecture, but computing in general, memory is a device that stores information such as data or programs that are available for use by a computer. These can take on the form of volatile memory, such as SRAM or DRAM, or non-volatile memory, such as hard disk drives or floppy disks.

- Registers

- Registers are a form of memory storage that are quickly accessible to a processor. Their overall functionality is often defined by the ISA.

- ALU

- The arithmetic logic unit (ALU) is a combinational digital circuit that performs arithmetic and bitwise operations on integer binary numbers.

- Stack

- A stack is a collection of elements that support two main operations: push (adds an element to the collection) and pop (removes the element at the top). Due to these, a stack can be described as a last in, first out (LIFO) structure.

- Accumulator

- An accumulator is a special register which stores intermediate results computed from an ALU.

Classification of ISAs

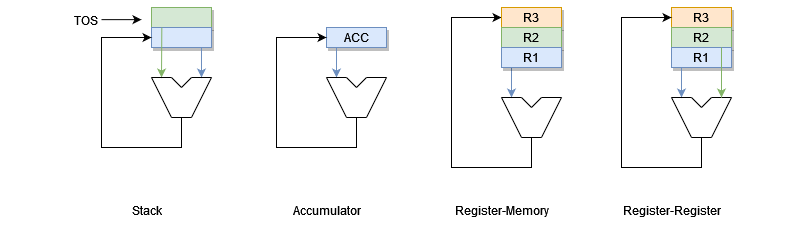

For the most part, every processor that has been fabricated work the same: they fetch, decode, and execute instructions. The major thing that differentiates processors is the type of internal storage it uses.

The major choices for internal storage are a stack, an accumulator, or a set of registers. Each of these different types come with pros and cons, and will be discussed once each have been covered.

Stack Architecture

As the name implies, this type of architecture makes use of a stack for its internal storage. As such, two instructions that are supported by default are push and pop, and they take one operand each: a memory address.

Arithmetic operations, such as addition and subtraction, are also supported. These types of instructions do not take any operands, as they end up popping the top two entries on the stack, perform the operation, then push the result to the top.

Below is sample instructions demonstrating how two values, stored in memory addresses A and B, are added together then stored in memory address C:

1push A

2push B

3add

4pop C

Accumulator Architecture

This type of architecture makes use of an accumulator. The type of supported instructions are load and store, which are for memory access, and arithmetic operations. All instructions in an accumulator architecture take exactly one operand, which are memory addresses.

Below is a set of sample instructions demonstrating how to add two values. The first value is loaded from memory via address A, then the add instruction is used to add the value in memory address B to the accumulator. The result is effectively A + B. This is then stored to memory address C, wherefore the value in the accumulator is reset back to 0.

1load A

2add B

3store C

Register-Memory Architecture

A register-memory architecture is one of two types of a register architecture. It's defining characteristic is that memory access is supported by all instructions.

The basic instruction support are load and store for memory access, and arithmetic operations. The former two take two operands, but the latter set of instructions take three operands, broken down as follows:

1load <reg>, <reg | addr>

2store <reg>, <reg | addr>

3ALU <reg1>, <reg2 | addr1>, <reg3 | addr2>

For arithmetic instructions, <reg2 | addr1> and <reg3 | addr2> are source operands, with <reg1> being the destination operand.

Below is a set of sample instructions demonstrating the addition of two values. First, the value stored in memory address A is loaded into register R1. After, the value stored in register R1 is added with the value in memory address B, with the result stored in register R3. Finally, the value in register R3 is then stored into memory address C.

1load R1, A

2add R3, R1, B

3store R3, C

Register-Register (Load-Store) Architecture

A register-register (also known as a load-store) architecture is the second type of a register architecture. It's defining characteristic is that memory access is restricted solely to load and store instructions.

As with a register-memory architecture, it also supports arithmetic operations, which require three operands:

1load <reg>, <addr>

2store <reg>, <addr>

3ALU <reg1>, <reg2>, <reg3>

Again, similarly as a register-memory architecture, for arithmetic instructions, <reg2> and <reg3> are source operands with <reg1> being the destination operand.

Below is a set of sample instructions demonstrating how two values are added in a load-store architecture. The values stored in memory addresses A and B are first loaded into registers R1 and R2, respectively. Then, those values are added and stored in the destination register R3. Finally, the result is stored from register R3 to memory address C.

1load R1, A

2load R2, B

3add R3, R1, R2

4store R3, C

Why Study the ISA?

It's important to be able to understand basic design principles for ISAs for the primary reason that it defines a hardware-software interface for an entire generation of processors. In other words: if a bad design choice is made in one generation, you will be stuck with its consequences due to maintaining backwards compatibility.

In fact, the design choices can have drastic effects towards the memory cost of the machine, the complexity of the hardware, and any possible compiler and programming language issues. These are discussed within the scope of program state, instruction semantics, and instruction formatting.

Program State

In computing, a system is described as stateful if it is designed to remember preceding events or user interactions. If a computer program is unable to remember preceding events, say an arithmetic operation, then the work done is useless. A big question is thus: how is program state managed?

For a processor, state is managed via its internal storage. Three types have already been discussed: a stack, an accumulator, or a set of registers. Each one comes with their pros and cons. For example, stacks and accumulators are good if memory is expensive as these types of ISAs allow for a compact instruction format. On the other hand, registers are faster than memory: this allows for fast reuse of values and flexible scheduling of instructions. This latter benefit is exploited for instruction-level parallelism, which will be discussed in a much later post, but keep that in mind for now.

In the context of a register architecture, the ISA defines the number and types of registers available for use, while also implementing any built-in mechanisms to manage errors, typically through exception handling.

Instruction Semantics

In general, semantics is the study of reference, meaning, or truth. Within the context of ISAs, and by extension computing, it deals with the meaning and effects of instructions on the state of the computer system. These range from simple arithmetic and logical instructions to data transfer and control flow instructions. Of course, these are just a small possible subset of all possible categories that instructions can fall within.

When it comes to design choices, instructions can have a high or low semantic meaning, which is analogous to the complexity of the instruction. For example, a load instruction in a register-register ISA has a low semantic meaning, as it strictly loads a value from memory to a register. However, in a register-memory ISA, the load instruction has a higher semantic meaning as the second operand can either be a register or a memory address.

An overall good rule of thumb to keep in mind as we move forward is that one often gains more by risking more. That is to say, by increasing the semantic meaning of a set of instructions (in other words, make them more complex), we can allow them to do more work at once.

Instruction Formatting

The previous two sections that were discussed will ultimately determine the way how instructions are formatted. Formatting, in this case, concerns itself with three major choices: syntax (i.e. bit encoding), width of the operation and operands (if applicable), and whether the instruction will be of a fixed- or variable-width.

As an example, consider a 32-bit machine. At most, an instruction will have to be 32-bit long. In the case of the ISA allowing variable-width instructions, there could be entire sets that will be within 8-, 16-, and 32-bit wide. These different widths will ultimately impact the width of the type of instruction (i.e. operation code, or opcode for short) and its operands, if applicable. These questions thus leads towards the case of instruction syntax: how will they be encoded?

Once an encoding has been decided, this also leads towards its decoding. Instructions with a higher semantic meaning will have a more complex encode/decode scheme as opposed to those with a lower semantic meaning.

What's Next?

A lot has definitely been covered so far, and it is perhaps a good stopping point to allow for digestion.

The next part will concern itself with memory addressing.